|

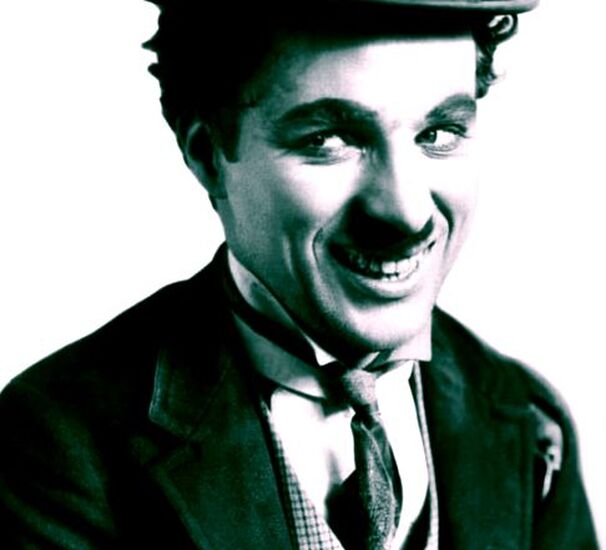

From almost the moment of its release, Taika Waititi's JoJo Rabbit has been the subject of controversy. It's crime, portraying Adolf Hitler as a bumbling fool and the imaginary best friend of the film's main character ten year JoJo Betzler (played by Roman Griffin Davis), a young Nazi in training. There is really no end to the holier than crowd currently writing movie critiques for a living. One said that the movie separated their ranks into hipsters and those who don't understand the inside joke, and that although he got the joke, he preferred to count himself among those who didn't. He also offered up the idea that the hipsters think they are the superior ones, and it's the sanctimonious ones who really understand what's going on, making it necessary for him to stick the little criticism of the movie as making light of something that should never be considered funny. This is more than a little like saying that Shakespeare should be placed in a dungeon by the followers of Torquemada. Given today's political polarization, I suppose it's to be expected. But I have to wonder if these apparently prim and pious blatherers (the hipster contrast is fucking ridiculous) would ever understand the irony of projecting Nazi like motives on almost everyone and everything who disagrees with them on the issue of ideological purity while failing to recognize their similarity to the dangerously zealous Dominican inquisitor mentioned above? More strangely, is the their ignorance of both the historical development and the intimate relationship between tragedy and comedy. The Greeks, who came up with both genres, believed that they referenced the natural forces of death and destruction, or negation of life. Tragedy teaches us to embrace the "destructive negation of life and culture" so that we can later "receive the blessings of pathos and humor, in that both teach about the necessary limits of form." In other words, in the Greek view, they were two sides of the same coin. In the Greek religion parodies always followed a trio of tragic presentations to show that, "Ecstasy and joy were just as much a part of Dionysian worship as fatal destruction." Once the parodies became separated from the tragic performances, it became harder to recognize the spiritual significance of tragedy. Which is exactly what is happening today. This means that these critics are either inserting their own political bias into their critiques, they feel they have to display their wokeness credentials in every piece that they write, or they're afraid not to do so. In either case, it causes them to lose, at least some perspective if not all, of the object at hand which is judge the film as if Joseph Stalin wasn't personally waiting to hear if your views matched his own. Visually, the film is something like what you'd expect from the Coen brothers or Quentin Tarantino, brightly colored and visually arresting. It contains great amounts of the kind of humor found in The Big Lebowski but mixed with the tragic elements of No Country for Old Men. It differs from Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds in its love for humanity, and in its overall lack of hatred in general. Imagine that. Waititi himself plays the imaginary Hitler who at first happens to be the BFF of the young protagonist. He portrays him as a bumbler who is full of advice, all bad, and someone who is so narcissistic that he depends on affirmation from the childish and naive. Strangely, this is the principal bone of contention with those who more acclimated to serve as hall monitors than write about films. Hitler was a dangerous fool and a narcissist of the highest order, and he couldn't never have caused the damage he did without the help of the criminally naive. Waititi uses him to show how the young, innocent, and naive can easily be misled by the pressure to conform. His relationship with the child JoJo shows just how youthful innocence can so be easily corrupted. Elsa Korr, the teenage Jewish girl (Thomasin McKenzie) being hidden by JoJo's mother Rosie (Scarlett Johansson) nails it on the head when she tells JoJo near the end, "You're no Nazi, Jojo," something that he was struggling hard to discover for himself. Sam Rockwell gives a great performance as a conflicted, gay Hitler Youth camp commandant and party leader. He presents his character as being both insane yet somehow more realistic than the people around him, a sort of a crazy Nazi version of the Eddy Albert character in the TV show Green Acres. He plays his character as someone driven into alcoholic absurdity by his surroundings yet still sane and moral enough to fight against the evil he has sworn to protect. This character states rather emphatically that most men are never one hundred percent of anything, neither evil or good, and that even the worst of us, can in moments of remorse, redeem our soul by selfless actions. (Hell, that idea was stolen from Dickens and the Tale of Two Cities.) This is embodied in the hope that most humans cling to with fierce determination and without which the human race would condemned to eternal darkness. Captain Kienzendorf, Rockwell's character, is something straight out of Dostoevsky and Russian literature, something that the more contentious critics seem to have missed. I wonder if they would dare to write a critique of The Brothers Karamazov with a warning that it presented the Devil as both a comical creature and the essence of banality? I also dare these word weasels to explain how the scene where JoJo discovers his mother's fate as conveying anything other than the extreme meaning of tragedy and the consequences of unfettered ignorance, hatred and cruelty and which should have been more than powerful enough to destroy any of their other petty considerations. JoJo's final confrontation with his demented imaginary friend is an absolutely brilliant scene. It represents the battle that takes place in the mind of all of us when we have to deal with the conformist pressure that social realities place upon our need to judge our self as being truly worthy of existence. It also reflects that such monsters as Waititi's Hitler are very well capable of playing any side of the social, religious, economic, or political fence. Maybe that is the real issue involved. I recommend this film. I assure that you will be stunned into a moment of silence when it ends, and that most viewers will come away with many, many diverse interpretations both political and otherwise of what they saw on the screen which is how art should always be. This movie will certainly make you think. Please do. Generally, we don't need people like humorless movie critics to help us decide if all short bumbling men with tiny mustaches should always symbolize the terrible evil of men like Adolf Hitler or the heart tugging pathos of Chaplin's Little Tramp or something in between. Most of us are perfectly capable of making that distinction on our own. Source: Myth and Philosophy: A Contest in Truths, Lawrence J. Hatab |

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed