|

Effective communication in basketball is a vital aspect of the game that coaches strive to develop among players. However, modern societal trends have hindered this process, often younger generations from the wisdom of the past and undermining their ability to communicate effectively. Coaches face the challenge of guiding players towards meaningful communication on the court, leading to improved teamwork and success.

Communication, as distinct from mere talking, is essential in basketball. It serves as a reminder of the necessary actions to develop skills, similar to rote multiplication drills used in teaching math. However, mindless repetition can diminish the value of this approach. Coaches now emphasize the need for genuine communication, where players convey their needs to teammates and provide support and instructions to fellow defenders. College coaches seek players with leadership qualities who can contribute actively without constant guidance. The ability to articulate ideas effectively often leads to success. Conversely, a lack of communication can hinder the recognition of a player's capabilities. Therefore, players must understand the correlation between success and their ability to communicate knowledge and articulate their thoughts. Learning from mistakes is crucial for players to navigate game situations effectively. This process involves myelination, which enhances communication between the brain and muscles. To facilitate this, coaches should design drills that simulate real game scenarios, challenging players to recognize their responses and convey instructions to teammates promptly. Such training not only improves cognitive abilities but also enhances listening skills among teammates. The difficulty of effective communication should not discourage players. Challenging situations provide opportunities for growth, as players learn to resolve contradictions and make quick decisions. They develop mental resilience and gain knowledge about when to talk, when silence is appropriate, how to use non-verbal cues, and the significance of encouragement and praise in fostering teamwork. Effective communication is paramount in basketball. Coaches face the challenge of instilling genuine communication skills in players, enabling them to convey their needs and instructions effectively. Success in basketball, as in life, depends on the ability to communicate and its effect on there ability to play as a team.

0 Comments

Last season, I wrote an article that was essentially concerned with reconciling the problem of wanting to play at a high rate of speed and yet maintaining the benefits of possessing the ball. Here are the ten key points I tried to make in the article.

Every now and then I drag out an old magazine or book from my basketball library and reread old stuff trying to come up with new ideas. There is so much information out there for coaches nowadays that it can actually be a little overwhelming to try to glean through all the bullshit trying to find anything of actual value. Suddenly, everyone thinks they're John Wooden or the basketball equivalent of Sir Isaac Newton, presenting their ideas as if using an extra cone or two in a drill is going to revolutionize the game. I'm a firm believer in the idea that you have to keep learning or you'll stagnate and die, but I've come to realize that the most valuable learning is going to come via a revelation or a change in your overall perspective rather than in some young muscle bound guy with a neatly trimmed beard and the annoying manner of a used car salesman inventing a way to have a cutter disappear for two seconds while cutting through the lane only to reappear under the basket (not that it couldn't be done).

I recently saw one young lady pooh-poohing the idea of centering your hand on the ball and of aligning your elbow. She even took a swipe at the need to place the ball's seams horizontally. She spoke with such great conviction and passion that I'm pretty sure she'll actually convince a bunch of dumb asses to add their off-hand thumb into their shooting form in an effort to correct the flying elbow and the knuckleball trajectory of random seams. I just muttered a disdainful curse word and figuratively broke wind in her general direction as I deleted her nonsense from my feed. I do find something of value on the rare occasion after deleting something like twenty morons for every one thing that I keep. Today's reading was taken from the May/June 2009 issue of Winning Hoops. I chose to blow the dust off the magazine because it had an article explaining Coach Walberg's Dribble Drive attack, an offense for which I've developed a kind of love/hate relationship. Coach W is a true innovator and has a lot of interesting concepts, but, in my opinions, he has way too many disciples. Jesus Christ only had twelve, and he set the world on its head. I think we could all agree on the fact that too many cooks spoil the, you know, whatever it is that too many cooks spoil. What I actually read was an article entitled Follow DeVenzio's 4 Rules for Winning Basketball. I don't know how much you know about Coach DV, but that dude could say more in a paragraph in one of his short pamphlets than most Coaches could say in one of their overpriced and over-stuffed with fluff, mainly self-glorifying, books. Take Rule No. 2 for example, "Always throw the ball to your own team." It sounds so dumb, but it is actually pretty wise. I've seen players on the junior college level, men and woman alike, who played like they never had a coach tell them to always pass to the outside hand away from the defense, or never to throw a fifty-fifty pass in between their receiver and the defender, or most importantly, in tight games, to make sure you put an extra emphasis in knowing the difference in what color jersey your opponent is wearing. There's a zen-like simplicity in the statement that covers a lot different things that can go wrong when passing a basketball. The item that really caught my attention though was a rule mentioned in a sidebar by a Dena Evans who at the time, was the Chairman for Point Guard College, the organization created by Coach DeVenzio. The side bar was about attacking a zone defense. The fourth rule was Use the Dance Rule which explained that the two weak side players had to constantly work together (dance) in attacking the middle of the zone from the back. The rule read, "The point guard needs to know that best way to beat a zone is to get someone the ball in the middle instead of tossing it around the perimeter." Talk about a lost tactic; in the headlong rush to reap the benefits of that extra point gained by making threes, a lot of people seem to forgotten the importance of simply getting the ball in the middle of the zone. It even enhances the three because inside-out passing increases the shooter's chances of hitting the three by a double digit percentage (according to a study commissioned by the NBA). Making threes can defeat a zone, getting the ball in the paint and under the basket can break the zone down at such a foundational level that the opposing coach would probably have to send the zone to seek the help of a professional therapist before he/she employed it in a game again. I've thought like this for most of my career. Three pointers are like attacking a castle where the arrows rain down on the defenders and strike an occasional defender who is foolish enough to be out walking around without his helmet during the attack. Shots inside the paint with their potential for drawing fouls are like huge boulders flung from catapults that crash into and demolish the walls of the castle. I even came up with a Tokien reference to prove my point. In The Hobbit, it was Bilbo noticing the tiny hole (over the heart) in the Dragon's armor that eventually destroyed the dragon when Bard put the black arrow (which had never failed him) into Smaug's heart and only after the defenders of Lake Town had wasted a year's supply of arrows trying to pierce it's scales and had basically given up the fight, accepted the inevitable, and started blaming each other and pointing fingers. At that point Coach Bilbo stood up from the bench and yelled at Bard, his star guard, to get the ball inside. You want to beat a zone? I'd suggest shooting it in its heart. There's a hidden message in Jesus's Parable of the Talents. Some will say that it's a lesson about the importance of approaching life with a maximum effort placed on becoming the best version of your self. Remember the way that Jesus tells the story is that the second servant, the one who brought back a fifty percent return, was sent alway in the company of the servant who did nothing. The only servant who was rewarded was the one who brought back a hundred percent return. This would lead most people to think that it's a kind of harsh way of putting things to say only the maximum effort gets rewarded. The only people who are built like that though are the true spiritual warriors, people who are capable of facing deprivation, approbation, condemnation, pleasure and suffering with a nary a smile, a grimace or a grunt. Life is fucking hard and so is making life decisions. Using that metric would condemn most of the humans who have ever lived to slinking out the back door with that servant who sat on his/her ass and smoked meth all day instead of taking care of business.

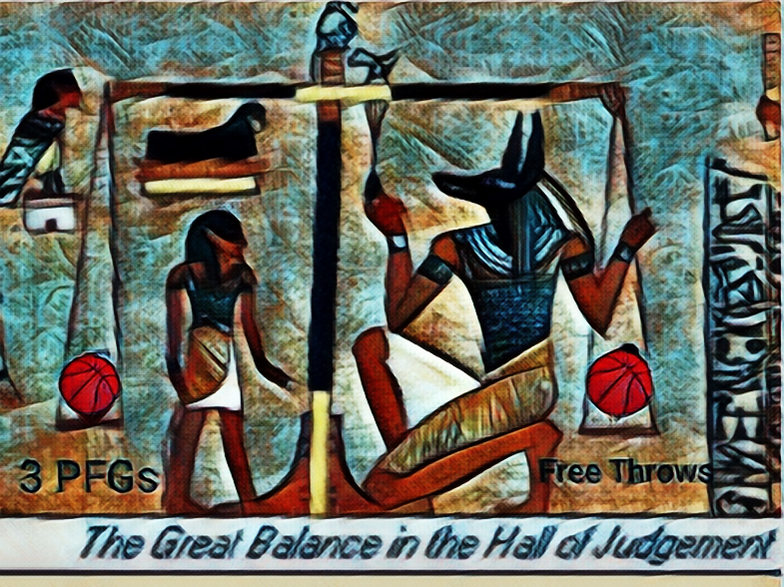

I understand there is a reason for that last servant bringing back double what he/she was given at the beginning. It's the goal, perfection is always the goal. It keeps us always headed in the right direction, but as a requirement for living it would cause most of us to give up the fight knowing that we could never rise to meet the standard. Christ also emphasized the need for us to be as wise as serpents and to me that shows he knew that at times, most people are going to come across situations where they have to strip down to their undies and wrestle with the pigs. The key being that you can't succumb to the praise of all those who witnessed you vanquishing the pig and in always understanding that getting mud on your underwear is infinitely different from getting mud on your soul. There's a reason why Jesus didn't place a servant who returned 75% of the money in the story. It would have exposed the real secret contained in the message. He was telling his disciples that they have to do some of the work themselves. He was telling them he couldn't just spoon-feed the information to them because they would lump it in with the news about somebody's complaints about their warts or all the gossip going on in Jerusalem in the day. It was also a litmus test to determine which ones would be able to understand what came next. The Dogon tribe of West Africa possess an extraordinary knowledge of the Cosmos and feel that it is their duty to protect and pass on that information. They are willing to teach anyone their secrets regardless of race, gender, age, or religious background providing that the seekers are able to ask the appropriate question to access the next level. It's the same thing as Jesus was doing. Spiritual seekers will recognize teaching in parables as a way to keep the material world from corrupting the message. All year long, I struggled to get our team to understand the value of getting to the line in order to become a championship caliber team (In truth, it has been this way for years). The problem is that most people always want to do things the easiest way possible. You fight against human nature when you tell them to make things harder on themself. This team was very good at shooting the ball, including the mid-range jumper. We were killing people without getting to the line. We had such good shooters that it caused me to have to re-think the rules that I have always taught about how to win the championships. We even changed our offensive thinking, which was predicated on attacking to basket off the dribble, to better accommodate their ability to shoot. In the past, I would never let my players shoot us out of a game. If we missed two shots from the perimeter, I would call a set play designed to get us a lay-up or to get us to the foul line. The rule we had was that we had to break the string of negative possessions where we came away with nothing to show for our efforts. I've always figured that the quickest to go from a closely contested game to being behind by ten points was to lose control of the flow of the game by creating long rebounds that ended up as lay-ups at the other end. Getting to foul line, even if we missed the shots, at least gave us a positive result (inflicting a personal foul on the opposition) rather than a zero. It seems like a minor thing, but it is actually quite important. Usually, you'll make at least one of the foul shots (another positive result). Many times though, you'll not only make the foul shots, but you'll make the lay-up and get the and one as a bonus, that is the three point play in addition to inflicting the foul on a defender, stopping play in your favor so you can control the flow, and breaking the string of negative possessions. Author Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has written an important work entitled Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. It outlines the results of a study detailing how successful people, including athletes, go about producing the necessary psychological state to achieve maximum success. He calls this the flow state, a state of being where our intrinsic motivations are in line with our efforts to be the best, i.e. (return the maximum results). Gaining something as seemingly insignificant as inflicting a foul on the opposition keeps your efforts on the positive side of the equation. Stringing a series of such positive outcomes together increases both the velocity and the amount of the positive energy being released thereby creating the flow state whereby things naturally appear to work out for the best. The problem is that in championship games both teams are always fairly evenly matched in that they, knowingly or not, practice the same flow techniques that Csikszentmihalyi mentioned in his groundbreaking study, so that championship games usually come down to one key play or a series of a few plays where both teams are exerting maximum effort at the same time. This results in a situation where one of the teams is going to give that 51% effort that tips the scales in their favor. I saw this happen in the CCCAA Junior College state championship games recently. In one of the games, the battle was back and forth when a player from the losing team made a hard drive through the lane. She had made several pivotal plays in the game before, but this time, she avoided contact at the end and missed the lay-up. I think that had she leaned inward and gone for the contact she would have been fouled and came away with two important free throws. It wasn't that this one play caused her team's eventual defeat, but it was part of sequence of coming away empty in game that was going to be decided by who kept the needle in the gauge on the positive side the most. During this season because of our ability to shoot the mid-range jump shot, I had changed my original dictum from "do not shoot the three until we have created an inside shot and possible foul" to "do not miss the outside shot until we have gotten to the foul line". Some might consider this to be a trivial, maybe even silly distinction, but it's really not. It still allows for an outside shot from a player who is very confident in their ability to make the shot in that situation, putting the onus squarely on the miss, and at the same time, it lets your players know that when that fifty-fifty collision, the struggle for control of the line to the basket, occurs on the way to the basket, they need to be willing to push through to gain that 51% advantage that ultimately decides the play. We had gotten all the way to the Final Eight with the new offensive strategy but failed us in the end because we couldn't make shots or stops. This led me to think about things on my way home from the Championship Tournament. What I came up with is that it is still best to stress the importance of developing a good first step, attacking in straight line drives, and finishing strongly while drawing contact. Championship games especially have certain inexorable rules. I once heard that in the local prison there a system of cables that carry the electricity to operate the security devices and electric fences. I heard that the guards daily have to go pick up the dead birds who can't read the signs that say to not touch those cables upon the pain of death. These kind of rules aren't meant to curtail freedom or to punish those who can't read. They exist to let people that some rules need to be followed simply because the results of non-compliance are so odious. Getting to the line in championship games is one of those type of rules. So, you may be asking yourself by now what does the Parable of the Talents have to do with teaching of basketball. I don't know, it's in there somewhere. I'm going to let you figure it out. One of the most important lessons I ever learned in basketball, I learned by sticking around on a Sunday to listen to Hubie Brown speak at the Nike Clinic in Las Vegas. Normally, I left first thing Sunday morning because I always had to work the next day and wanted to get home in time to rest up. The motto for Las Vegas is, "What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas." But what usually stays in Vegas is your money and your health. Back in the days, the Clinic was mainly a three day drunk. It was nice though, to have the basketball sessions to break it up.

If I were speaking to a newbie, the first thing I would tell him or her about clinics is that you don't need to listen to everybody and you don't have to write everything down. Not all them sumbitches have anything of value to say. Big Time college basketball is a lot like your own association, some of them coaches are worthy of being called Coach, and some ain't. It ain't equal, no matter what they tell you. If you go and sit there everyday for every session, you're just showing people that you ain't the brightest bulb in the world. Fact is, sometimes you can learn just as much about basketball with the thinking that goes into figuring out whether to raise an Ace high playing Texas Hold'em. All you're going to get from sitting at a clinic all day is a callus on your ass and bad case of writer's cramp. If you come away from a clinic with one good insight that helps your program, it was a good clinic. If you come away with two or three, it was great clinic, and if you win some money, that's icing on the cake. The best thing about clinics is the networking that goes on. Its hard to turn down someone asking for a favor, when they've seen you wearing a trashcan on your head urinating on metal sculpture painted to look like a cactus. The only two coaches, I've ever heard who could make me violate my own injunction against writing everything they say down, were Hubie Brown and the late, great Don Meyer. Both of them dudes could spray out helpful ideas faster than Eminem could spew out nonsensical rhymes (that dude could say more dumb shit in a minute than a typical Baby Boomer could come up with in a week). Hell, Hubie's throw aways were usually better than anything and everything anybody else said at the clinic. I came away from that session with two things that changed the way I looked at basketball. He was the first person I ever heard say that a good rule of thumb was to always make more free throws than the other team shoots. Think about it. It makes a great deal sense. It summarizes the idea that you want to get fouled, and, at the same time, you don't want to foul. It seems kind of simplistic I know, but I also know a lot of coaches who haven't figured out its simple truth. In fact, I just read a story where Jim Boeheim said about Syracuse's recent loss to North Carolina, that they had done everything they could do to win. Later, he said his team had only shot three free-throws compared to North Carolina's twenty-three foul shots. Got news for you, Jimmy, you didn't do everything. You should have stuck around to listen to Hubie too. Coach Brown was the first coach who I ever heard talk about the importance of controlling the pace of the game, to make sure the pace fits what you were doing and not favor the opponent. These two points became the core of my approach to the game. From that point on, I always emphasized the need to be able to get to the rack and to draw fouls. If we came away empty on a couple of trips down, we would go inside, or attack the rim trying to create the and one situation. In turn, this would also help us control the pace. Whenever we went to the foul line, I would wait until right before the ref handed the shooter the ball, and then sub. That way, when we made the free throw, the clock would stop while the substitution was made, and we could not only get into whatever defense we were running, but it helped put us into control of the clock. Usually, we would press because pressing forces the other team to react to what we were doing and gave us another way to dictate the pace. We often released someone long on the shot (cherry pick) because that would force their defense to get back quickly and helped us to decide the pace that the game would be played at, and if we went up against a team that transitioned well, we would keep an extra defender back to guard our basket and slow down the early break with the idea being, we run; you don't. It's pretty hard nowadays to teach these concepts because everybody and their dog just wants to shoot the most threes. I'm learning to love the three pointer though, and I wish that we always shot the ball well enough to not have attack the basket in order to draw fouls. The way I see it though is like although I keep a tire jack in my trunk, I hope I don't ever have to use it. But if I do get a flat, I'm going to be awful glad it's there. He still thinks he knows it all; I've always knew I didn't. It's really kind of weird to think that in writing about the essence of basketball, the first thing you would list in order of importance is not a strategy, a game plan, or a set of plays. It is an attitude that applies to nearly every aspect of the game, but also to life in general. It's all about survival. It's always been about survival, and there's nothing that will ever change that. We have created veneers, coverings, facades, and self-justifying thoughts, anything that covers us from detection. In a perfect world, our insides would align with our outsides and that union would produce a glow. Most of us don't have that glow, but wish that we did. We live in a strange world, a world of infinite distractions, information comes at us at a dizzying rate and it's harder than ever to maintain focus in the effort to find the truth about things.

We are mainly here to learn. All games, including the game of life, are ultimately chess games. The problem is in basketball, as well as life, most people are playing checkers. Some people don't even know the rules of checkers. Relationships are usually the highest form of chess. My wife and I always were playing checkers though. When the game got overly complicated, she pretended to spill her wine and while I was getting some paper towels, she flipped the game board over. The sad thing was that the game didn't just come to a sudden end though. It didn't even end when she died of cancer eleven years later; I just started playing both sides of the board.

Even games as simple as tic-tac-toe have deeper levels of significance. Regular tic-tac-toe is a simple game of position, and if both players are aware of the basic strategy of how not to get beat, most games should end in a draw. In order to gain victory in such a game you need to play against someone who is not overly bright or come up with some kind of random, outside-the-box thinking like telling your opponent to 'look over there!' and marking a square when they turn around and look. I remember once reading about how a Japanese master swordsman (the guy in The Five Rings), when meeting a very dangerous rival, showed up an hour late carrying a wooden sword. The strategy worked. I sometimes resorted to such tactics. When I was coaching JV boys, we once came out to warm-up to Wagner's Die Valkyrie, with all of it's militaristic overtones. Another time, my girls came out to the blaring bag-pipes of a Scottish battle song, and, in another important game, the girls didn't take the court until right before the game started, having warmed up in our small gym and entering the locker room through a side-door. I did all of those type of things more to pump up our girls rather than as some psychological ploy to knock the other team off balance. I wasn't really sure what effect it would have, if any, upon the other team, and I only wanted to use things I knew that would reward the effort made. After that, we did, however, start warming-up in the small gym for all of our really important games, not only to get the girls psyched up, but also getting some extra shooting in and going over the changes that we planned to use against the particular opponent, you know, tangible stuff. As a scout, I see an awful lot of high school games, and I'm noticing there seems to be a lot more coaches nowadays playing checkers, who, in turn, produce a lot of checker playing players instead of players who are capable of understanding the parallels between basketball and chess. I see a lot of girl's games where the coaches just let the girls do whatever they feel like doing, sometimes producing baskets and steals, but more often than not, producing misses, turn-overs, and hard-to-watch basketball I watched a boys' game recently. The team that won is almost assured of finishing with at least twenty wins. The team has some good players with two bigs, in particular, who should be able to play after high school. Their opponents were much shorter and pretty much out-manned from the start, but after half time, the losing team, being considerably behind, came out and started trapping everything. It was a good decision on the coach's part as he had a couple of hot shooting guards who needed to get more engaged. The other team got sucked into a track meet and a pace that worked to their disadvantage. I figure that the coach was probably thinking that he had players who could handle the ball and shoot as well as the other team. He was probably right too. The thing that he didn't seem to grasp was although he had shooters too, he also had the bigs and the other team didn't. That meant what he should have done is slowed the pace and rammed the ball inside to draw fouls which would have left his team in control of the clock. They eked out a close win in a game that shouldn't have been close at all. Getting sucked up into a guard orientated running game when you have the clear advantage inside is like playing the hard ways on a crap table. There's a reason they're called the hard ways. It looks cool when they hit and you get to yell a lot, but the people who know how to take advantage of the odds on a craps table ain't making those bets, they're for the drunken tourist crowd. I saw another game recently where two top-ranked girls' teams were playing. The visiting team's strength was predicated on their stifling full court press. The home team had obviously been experiencing some success versus that type of press by placing their big under their own basket, letting their guards break the press, then attacking the basket and passing to the big for an easy lay-up. The problem was it wasn't working against that pressing team though, and the guards kept turning the ball over for easy scores at the other end. I had just seen another team play against this same press by placing their big in the middle at half court, and they had no problem getting the ball into the middle, diving their wings toward the basket and scoring lay-ups against it. The lesson to be learned evidently was that what works against one team doesn't always work against another team. That's a chess lesson right there. I didn't stick around after half-time to see if the home team's coach ever decided to abandon the checkers strategy and move to capture the center of the board like real chess players are taught to do. The big problem when you have coaches who only teach the basic skills like shooting, making lay-ups, or ball handling and who use the same offense and defense game-in and game-out, is that they will never learn the importance of taking calculated risks to see if their ideas work or not. If they do, you add them to your bag of tricks; if they don't, you try something different. That way you learn not only to be prepared for most events, but it also teaches you how to teach your players how to think about what they are doing on the basketball court. Teaching kids how to handle the ball and make lay-ups is a checkers skill; teaching them how and when to use a first step move in order to draw a foul is a chess move. Teaching them how to pass into the post is checkers; teaching them how and why to screen the middle defender in order to breakdown 2-3 zones from the inside out is something that is borrowed from chess, a much neglected chess skill I should add. I remember years ago watching Marvin Welch, the legendary Woodlake coach, place two rebounders on the weak-side boards. I had also read a study back then that stated that 70% of all rebounds taken from one side, end-up coming off the weak side glass. So, doubling up the weak-side boards is a chess move, not doing it, is playing checkers. When you're on defense, teaching your players where to go on 3 pt. shots from the wings and teaching them to treat every shot as a miss and an opportunity for a rebound is a chess move; having them figure out on their own which shots need to be rebounded and which ones don't, is playing checkers, and playing checkers badly at that. Most of the girls playing for us now have never been taught about the importance of controlling the pace of the game (chess move) so that the the flow of the game matches what they do on offense. That is just a smart thing to do; playing at pace dictated by your opponent is not. One of the ways to control pace is to teach your players how to set their defender up for a blow-by and attacking the rim to draw fouls. However, we have shot the three so well that we have won 90% of our games without making much of a concerted effort in getting to foul line. It's that 10% of our games though that will decide if we make it back to the Final Eight. Depending on your three point shooting when your threes aren't falling in a big game is the basketball equivalent of praying for success to an idol made of bricks. A cheesy analogy I know, but you get the picture. One way you hope that your shots start falling, sometimes it works, and then there's the other way, where you take active steps to keep the odds working in your favor. I once went to a boy's practice where the head coach had been the assistant at one of the best teams in the history of the section. When I walked in, they were running the very first zone offense I had ever been taught when I was coaching the B team boys at a junior high school, a simple overload where the high post slides low on a pass into the corner. I didn't walk away thinking that, "Damn, that Coach is a checker playing fool right there." What I did learn that day is that many times, keeping things simple is the chess move. Everything we do in life takes place in an infinite universe. That pretty much means that whatever we do has a damn near infinite variety of interpretations. Someone could do something that, on the surface, looks totally stupid and still have it work because of the time and situation. The first basketball lesson I ever learned about this subject was when I followed an old Chuck Daley aphorism, "Sometimes not to guard is to guard," and left a shooter wide open in the corner in order to sandwich a post-player who had killed us the game before. It worked then, and it's worked several times since. I used to have a weak-side double stack where I would a wing around the stack and out to the corner. I always marveled at how many times the coach, and often the fans too, would yell for the bottom zone defender to get out on the 'shooter' in the corner and leave the section's leading scorer alone on the baseline coming off a screen. To tell the truth, I've never really been all that great a chess player. My only claim to fame in that regard was when I once beat a guy who had beaten me regularly for years by sacrificing my queen knowing that if I made it look like I had made a mistake, he would jump on it without remembering that his rook was the only thing preventing me from checking him two moves. I won't even pretend that I know all that of the chess moves that there are available in basketball. Hell, like I said, they are pretty much unlimited. I do know that there aren't that many people who would argue against the logic of knowing that basketball coaches who understand that there is a chess gaming going on at all times have a very distinct edge over those who don't. And it only goes to say, that players who have been taught how to think that basketball is a chess game will usually prevail over the likes of those who only know how to dribble fast and shoot every time they have the ball regardless of whether they can shoot or not. Like I said, I don't know most of the chess moves, but I can recognize them when I see them, and I appreciate them greatly, and that goes double when they are done in the game of life and the game of love. You really have to admire those people who know what they are doing. When I first started driving back and forth to Visalia to coach at COS, I developed the habit of holding these imaginary conversations where I would debate particular people about things I felt strongly about. For example, there were many times where I tried to convince Christopher Hitchens, the most eloquent speaker I've ever heard, about the error of his atheistic beliefs. I realize when I'm doing this that I'm really just talking to myself, but I use this technique to whittle down my thinking to where my ideas can be best expressed while using the least amount of words. If I started getting too distracted from the main point, I would start over from the beginning.

I often use the same technique when I'm trying to convey an important idea to the kids I coach. Speaking in a pre-game or half-time talk we are usually pressed for time. So, on the way over to a game, I try clean up my thinking to where I can state the main point(s) in the minimum amount of time. We had a big game against Fresno City this last week, and I was worried about the outcome. The main reason I worry is the fact that the team doesn't make much of a concerted effort to get to the line. It's something I have stressed throughout my career. Somewhere along the line, I picked up an observation that said that one of the ways to guarantee success is to always,"Make more free-throws than the other team shoots." My experiences have often verified the truth of the statement. Over the years, I've seen a lot of teams shoot themselves out of games by continuing to shoot threes when their shots weren't dropping. I would swear on a stack of Bibles that the quickest way to go from a closely contested one or two point game to a ten point deficit is to string together too many non-scoring possessions because of three-point misses and the long rebounds they create. We had a rule; Miss two - Get fouled. It applied to both individual and team play. I would let the girls make their own decisions in our continuity until they came away empty a few times, I would step in and call one of our go-to plays to get the ball inside where we more likely to draw a foul. The reasoning for this came from a clinic where I stuck around on a Sunday, something I never did, to listen to Hubie Brown talk about the importance of controlling the pace of the game. The thing that usually kills you when you're missing threes is the long rebound that ends up as a lay-up at the other end. You lose control of the pace and suddenly your team is reacting rather than imposing their will on the other team, and, in turn, this leads to impulsive decision making and rash play when you most need cool heads and discipline. Stopping play on your offensive end, allows you to control the pace. Not fouling at their end also helps as does doubling up the weak-side rebounding area. Another strategy that serves the same purpose is waiting until the ref hands our free-throw shooter the ball before sending a sub to the table. That way, if the shot was made, the horn sounded and play stopped, allowing us to get into our press if we were pressing, or drop back on defense if we weren't. This usually helped put us in control of the game clock. It also allowed me to send in instructions via the sub without calling a time out or having to yell them out where the other coach could hear. In the game leading up to the big Fresno City showdown, we had scored 51 points on 43% three point shooting on the way to scoring 114 points for the game. We shot forty percent from the arc in the previous game and put up 115 points. We shoot the ball pretty well, especially when have big leads and there's not of lot consequences for our misses. However, missed shots and a lack of free-throws were factors in both of our losses. Earlier in the week, I started thinking of using the story of the Three Pigs and the Big, Bad, Wolf as an allegory to stress the idea of being better prepared for this game than we were for our two losses. If you remember, in the story, two of the pigs tried to cut corners and instead of being able to slam the door in the wolf's face, the wolf blew their shoddily constructed shelters apart and ate them. The third pig took the time to fully prepare and constructed a fortress made of bricks. I imagined the confrontation with the wolf going something like this: Knock! Knock! Who's there? (Barry White voice) The wolf. I'm hungry. Open the door! The pig rises from his easy chair, walks over to the door, opens the peephole, puts his lips to the peephole and says, "Screw you, Wolf!" and slams the little peephole door. The wolf gets angry and blows and blows, but the brick doesn't give. Eventually, the wolf blows himself out and falls down on the sidewalk, and the pig comes out and vanquishes him and starts using the wolf's tail to dust his blinds. The message of the story being that preparation is the key. We are generally well- prepared for games, but, it was our inability and unwillingness to attack the rim and draw fouls that failed us in our two losses. The problem is we score a lot of points without the rack attack. That shooting success caused me to re-think our emphasis on getting fouled. We did not want to give our players the idea that they shouldn't be shooting the ball, or that we thought that it wrong for them to be shooting threes late in the game in tight contests. I was trying to mold the Three Pigs thing into something useful and drove back and forth from Corcoran to Visalia talking to myself and trying to figure out a way to make the key points without sounding too trite and/or corny. The process wasn't going all that well. I was mostly thinking about how to explain why getting to the line was so important, even when we were shooting so well. Earlier in the year, I had told them half jokingly that it wasn't the shooting of threes to which we objected; it was the missing. It was the coming away empty handed from consecutive possessions that was the real problem. While driving to Fresno and practicing how to phrase what I wanted to say, I started to think about how my high school team used what we called The Flash Drill where a player in the middle of the key would have to keep a player from flashing from the weak-side low-post to gain position in the ball-side high-post. I was going to tell them about the lost art of the arm bar and how you don't ever use it with an open palm or to push off. You simply hold it in position, palm facing you, to bar someone's path toward the ball. The offensive player was expected to secure the post in such a way that the wing player could pass into her without resorting to a 50-50 pass where the defensive player would have a fifty percent chance of stealing the ball. The defensive player's job was not to allow the flasher into the high post. It was a tough drill that encapsulated two of the main points of our offense and defense, the high post is the most advantageous place to possess the ball because of the multiple passing lanes, and the defense should therefore never allow the ball to get into the high post. We ran that drill in the middle of our practice because it summarized every other aspect of our defensive philosophy in one drill. It contained the very essence of our get wide/get low close-out drills, all the mental toughness of our box-out drills, and the intensity and positioning of our denial drills. I realized that it also contained the essence of our offense. For some reason, that thought made me realize that what happened when the shots quit dropping was a mental issue. The basket grew smaller in the shooter's head when he/she starts to feel the pressure engendered by thinking about the consequences of missing. I abandoned the idea of using the Three Little Pigs analogy altogether. Instead, I explained that we shot so well in the games where we felt no real pressure and that we needed to maintain that pressure free shooting attitude in every game and every situation. I had always told them not to defend themselves, but this time added that instead of thinking about the consequences of missing, they should use the attack-the-rack mentality as an attitude adjustment to remind themselves and their opponent of their willingness to get a lot nastier on defense while ramming the ball down their opponent's throat in order to re- impose their will, regain control of the pace, and not have to resort to impulsive behavior and rash play. We ended up winning a very important, very hard-fought game. The girls were pretty impressive through-out and shot the ball very well. I don't know how much help, if any, that those words played in the win. These girls are a pretty chill bunch to begin with, they play hard and usually aren't afraid to shoot the ball. The process of thinking about what to tell them and how to tell it, did open up my eyes to the importance of attacking the rim in teaching how to re-rout their mental/emotional response to missed shots, changing a worried shooter into a stress free shooter. Or, in other words, how to build a house of brick before the wolf suddenly show up at the door. When I was a much, much younger coach, I had this weird ability to be reading something like the back of a Cheerios box and come up with basketball play inspired by something I had read. I've been through a pretty rough patch these last few years with my wife leaving me and later dying of brain cancer and my mom developing heart problems at the same time that I was dealing with my father's dementia. I couldn't afford therapy as they wanted $400 a month that I didn't have, so I did what most American males do in such situations which was try to fix things on my own. I made a hobby out of reading books about psychology, mythology, and spirituality.

I began to notice a lot of weird patterns and how a lot of things that we often take for granted in the material world are actually based on the laws of energy, biology, psychology, and physics. There is this book entitled The Master and His Emissary about brain structure written by a professor named Ian McGilchrist who argues that the more analytical left-side of the brain is jealous of the slightly larger, big-picture orientated right-side of the brain and will lie and manipulate things in order to seize command of our thought processes. The more spiritual right-side is ousted in a type of coup and afterwards the left, now unable to fully understand the full meaning of things, will run shit into the ground until it is necessary to hand the reigns back over to the right side to restore the proper balance. McGilchrist points out the ancients seemed to be aware of this situation and encoded it in their myths. He also argues that it is possible to look at history and recognize which societies were working with functional bi-cameral thinking and those time periods where all social activity was being governed by the left side only. The other day I wrote an article triggered by my efforts to explain to our players how their offensive thinking should be integrated with their defensive thinking. For example, they should regard defensive rebounding as the beginning of the offense, and their offensive efforts should in some way be governed by what the needs of the defense are. I swiftly recognized this as an example of fully functional bicameral thinking, and then later I noticed that the outline of the basketball court closely resembles the make-up of the human brain. The basketball court has two sides, an offensive side and a defensive side and the half-court line acts much like a corpus callosum in that it governs the interplay between the two sides. If the player is on one half of the court, they are in an offensive mindset, but the moment they cross the line, they are instantly governed by a defensive mindset. If a coach only focuses on one side of the game, say the offensive side, it could lead to an imbalance where their defensive choices are what gets them defeated. A perfect example would be when a team keeps shooting threes when they are not dropping and suddenly a few long rebounds leads to their defense being overwhelmed in transition. This makes the case for thinking in an integrative way where you need select an offense that serves the needs of your defense, and vice versa. Some people might say, "Well duh, that's totally obvious," but I don't think that's the case though. I think that most good coaches intuitively select offenses and defenses that are compatible, but don't delve into the issue much deeper than that. It is obvious how running a defense that limits your opponent's possessions is beneficial to your team's efforts to outscore the opposite team. Possessing the ball is clearly one of the best defensive strategies there is. But what do you do when your team is built to run? The faster you go, the more possessions and scoring opportunities the other team gets. Therefore, it seems that there would need to be some concessions made to offset the negative aspects that those increased opportunities offer. I think on the offensive end they would come from an emphasis on not turning the ball over, not taking bad shots, and extending the possession by getting offensive rebounds. On the defensive side, you would need to emphasize the need to force turn-overs, create steals, not foul, and control the defensive boards. Nothing too ground shaking. Understanding how defenses and offenses mesh and work together could help a coach when scouting the opponent. A key question that could be asked would be, "Does their choice of defense help their offense? If so, how? The right answer could give an idea of where to attack in order to disrupt this coordination. For example, say they run a fast paced offense but take bad shots and make risky passes and their defense doesn't put any pressure on the ball. A coach could counter by hanging on to the ball and running time off the clock limiting the opponent's possessions and dropping two back to safety positions on shots to neutralize the running game. I noticed the same pattern playing out in half-court situations. The side that the ball is on demands a more focus effort than the weak side. It is like the defenders on the half-line have to really focus where the ball is and only place a partial focus on what's occurring on the weak side (it is usually an effort to distract anyway), but once an offensive player tries to enter into the strong side there is a need for more of a focus. This seems to suggest that a player on the help line needs to learn to think of his/her defensive efforts in a more of a wholistic fashion, to grasp both the purpose of the play and how the individual parts serve that purpose. Defending the Corner Versus the Four Out A fellow coach and I had a long discussion a few years back about how to defend what I call the 'long line', or the passing lane between a guard with the ball on top looking to drive right for a lay-up with a teammate in the corner looking to catch and shoot the three after his/her defender goes to help stop the penetration. The difficulty in defending this action is one of the primary reasons that coaches run the dribble drive or four-out offense; it stretches the defense almost to its breaking point. At the time, I didn't think there was any one great way to defend that option, and I wrote a blogpost referring to it as a contradiction that needed to be resolved by which I meant it needed to be practiced, not so that the defender would ever master the skill, but the effort would at least help to increase his/her reaction speed and help them to get better at both stopping the penetration and recovering to contest the shot in the corner. In most cases, I still believed that by helping on the drive, the shooter would still get a good shot off, sometimes contested, sometimes not.

I now think I may have been wrong. I came home the other night from a scrimmage in San Jose and couldn't sleep. Later that night, I started thinking about that action. I think I was being triggered by something that happened in the scrimmage where the other team came down on offense, and we didn't have any body in the gap defending the pass to the girl in the corner. We we ended up breaking down and giving up an easy bucket. The girl who was supposed to be defending the gap was just to the right of the ball side block, lined up almost directly behind the ball's defender in order to stop the drive to the basket. I think she was worried about being back-doored. Suddenly I began to picture the right angle triangle involved. Seeing the triangle in my head helped me to realize that the defender needs to place him/herself between the driving lane and passing lane at a point where he/she can go from threatening the passing lane from a closed position with the denial hand held thumbs down. The moment that the dribbler tries to get by the ball defender on that side, the corner defender needs to open up to the ball, stay down and take two steps straight across to interdict the drive to the basket. It is important to emphasize the straight across movement as many defenders will make the mistake of moving upward toward the ball and thereby increasing the length of the recovery run. Arriving at the help position, it is important to still maintain a lowered stance, and sit across the driving lane at about a forty-five degree angle while pointing the inside shoulder toward where the free throw line and the opposite lane line meet. This staggered stance allows the defender to point his/her outside foot toward the offensive person in the corner. If the pass goes to the corner, the defender should push off on the inside foot and keeping their shoulders low take two big steps toward the corner. The threat of being back-doored can be mitigated by keeping pressure on the ball and having the weak side help defenders treating the action like a downside rotation drill, or the same as they would defend a baseline drive. Also, by placing their hand thumbs down in the passing lane, the defender gives his/herself an arm's length cushion to recover if the person in the corner disappears behind the defender's shoulder. Points of Emphasis 1) Two-steps- The defender's original position should be predicated by his/her ability to arrive at any of the positions needed by taking two quick steps either to the side or toward the corner. 2) Staggered help stance - The defender needs to turn their bodies to indict the drive at a forty-five degree angle which allows him/her to point outside foot toward the corner. This allows the defender to use the inside foot to thrust toward the corner. 3) Straight across - cut the driving lane directly opposite of where the passing lane is being defended. Do not run up to intercept the drive. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed